Learning Code — Tips on Research (and Repetition)

When you boil it down, learning to code is a lot like learning a language. Or rather, learning several groups of syntactically similar sub-languages that change all the time, most of which will inevitably one day be abruptly obsolete.

Pretty, pretty colors, VSCode. Photo by Luca Bravo on Unsplash.

If you’ve ever take it upon yourself to learn a second (or third) language, you figure out pretty quickly that picking it up is not usually an overnight deal. Languages have many learning challenges to be contended with: vocabulary and syntax are a lot more than just words put in the right order.

Words have denotation, connotation, and subtext, and grammar had depth and meaning that takes experience to appreciate. And that’s not even getting into intonation, pronunciation, and listening.

Language learners don’t learn the same way, either. Some excel at forming fluid sentences, while others are great at picking up vocab. Some have a great ear and can understand and replicate intonation and usage.

And just about all of them need to grind and grind and drill and practice before they get any good whatsoever.

Stop me if you’ve heard this one: code is lang–

What?

Oh yeah. I put it at the top, didn’t I?

How I Learn and Research Code

Learning code follows many of the same principles, and I have succeeded when I apply the same learning methods as I did when learning new languages. That includes memorizing the words (like data types, methods, and operators), drilling syntactic rules (like order of operations, synchronicity, asynchronicity, and conditionals) getting help from “native” speakers (from teachers, forums, guides, and documentation) and doing it over and over and over and over.

And over. Until I get it.

And how do you do all that? Well, the short answer is… Google it.

Google may be the salvation or doom of humanity. Or it might disappear into the night. Hey, every other world dominating empire did eventually. Photo by Luca Bravo on Unsplash.

But the actual answer is Google it, and all that other stuff that takes place before and after you fire up that eponymous search engine and hammer those keys to solve the problem of the day.

Step One: Foundation of Documentation

Before you set off to scavenge the interwebs for that piece of code you need, consider that it’s often better to build your new code on a strong foundation rather than just hammer a new snippet on anyplace you can. That starts with, yup, reading the documentation.

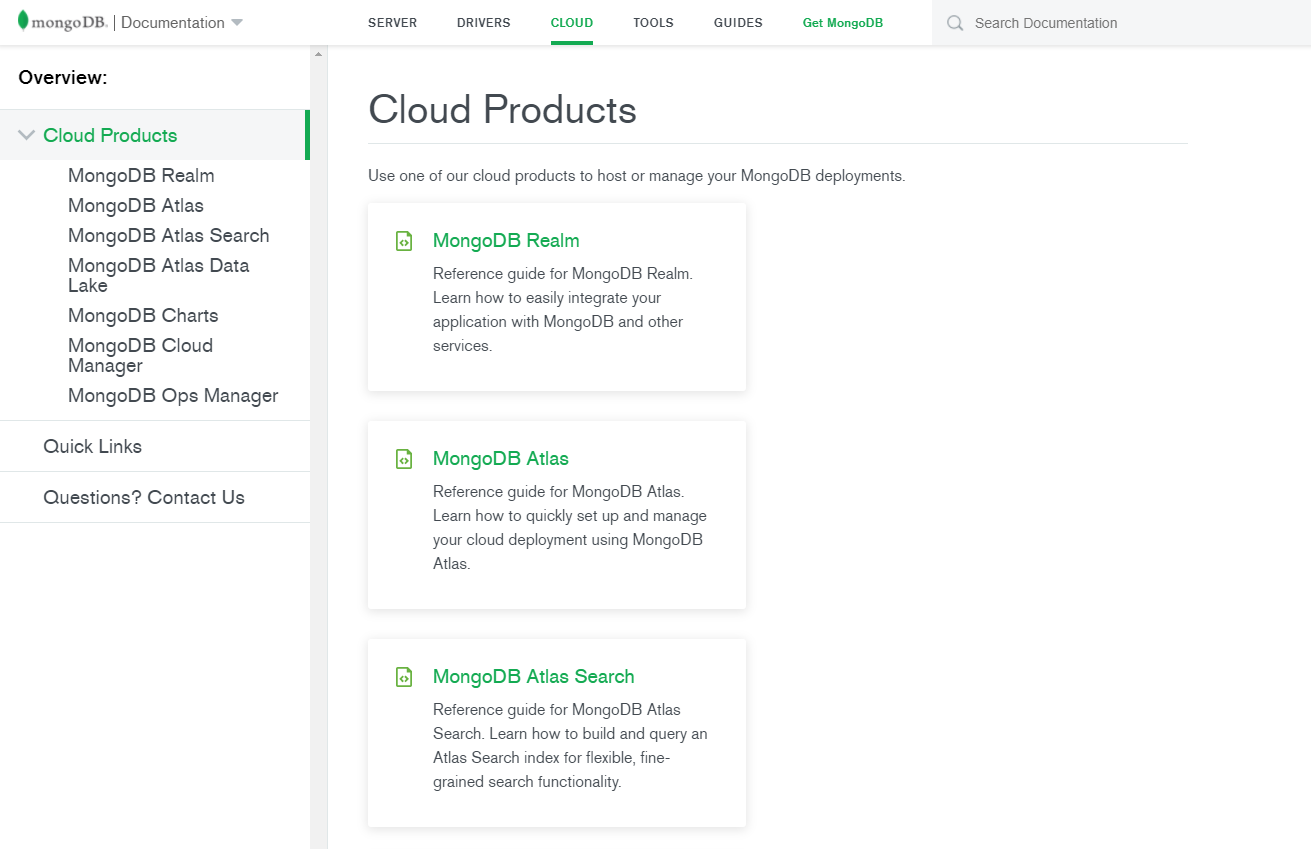

MongoDB’s documentation is neither exciting nor sexy, but it sure is useful for making a database in MongoDB. Photo from https://docs.mongodb.com/cloud/.

No one is saying this will be exciting. It’s basically a big ol’ list of rules and definitions with a few tidbits of example stuck between their teeth. But remember you don’t have to memorize every bit of it: reading it over at least once should give you the general layout, or at least an outline of the language. That way, the next time you want your code to do something, maybe a memory will spark, and instead of searching for “something that picks between choices” you’ll be able to plug in “switch statement” instead.

Google is not always especially good at parsing circumlocution (that’s your $50 word for the day), so having specific terms you vaguely remember saves you tons of time. If nothing else, it should send you down the right path.

Step Two: Make With the Google

Having the correct terms for research helps a ton, but sometimes you just don’t understand how their being used. You get what their definition is (at least partly), but it’s harder to conceptualize how they should be used.

It’s here that additional examples help a whole lot.

Like, a lot of them.

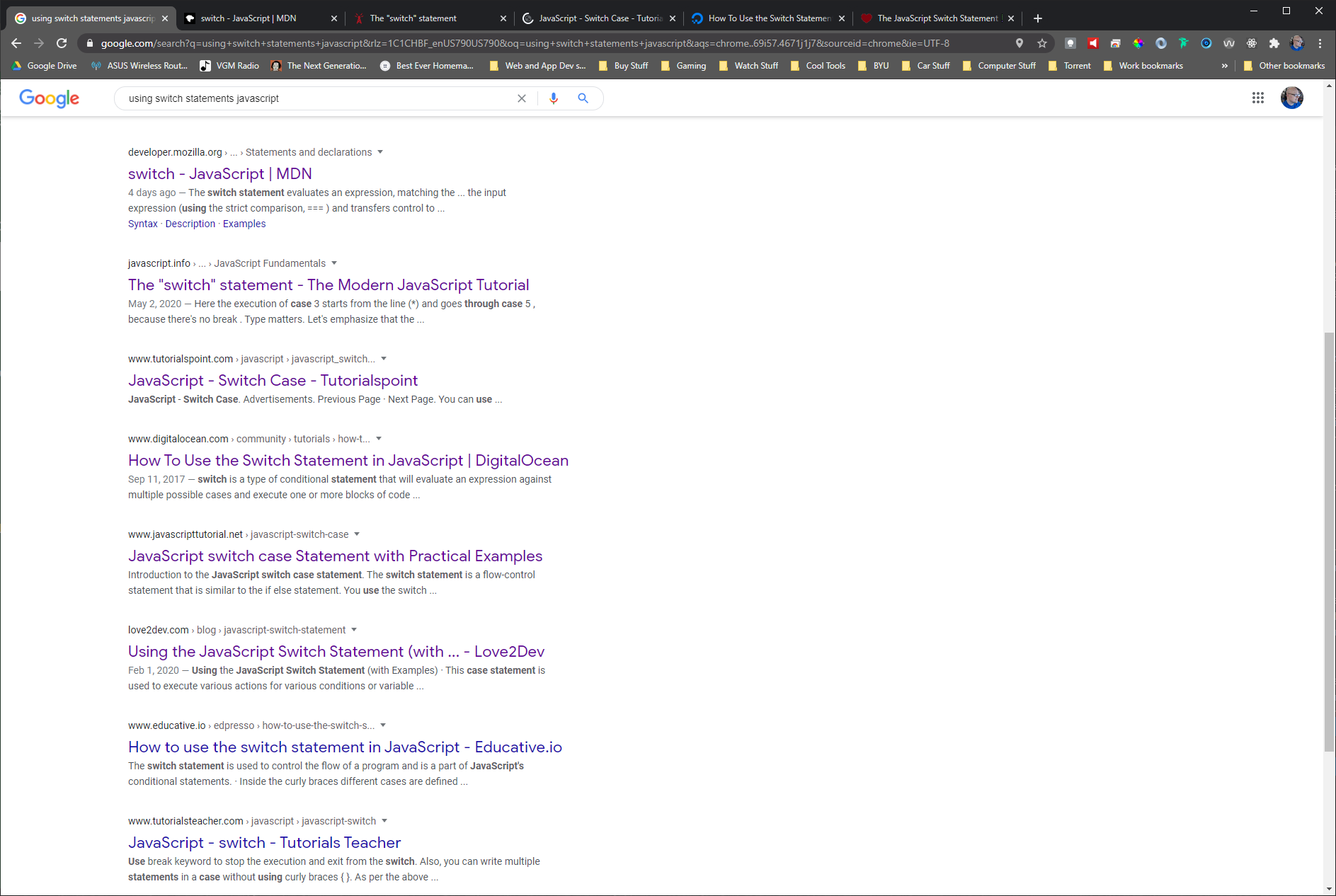

Most of the time when I’m trying to learn a new method/topic/form, I’ll open a minimum of five to seven sites on the topic (usually starting with documentation). Maybe the first one has all the answers I need, but even if it does, I understand the concept a lot better if I have other usages and examples with which to compare.

If your research on Google just picks out the first couple of entries, please consider expanding. Photo from https://docs.mongodb.com/cloud/.

From there, it’s grind time: read lots of posts, blogs, and Stack Overflows. Sometimes you have to doggedly scan forums for the info you need. Scanning is a good tactic to get to important info, but remember that when actually get to the pertinent info, focus in read it seriously.

Aside: Beware “Tutorial Hell”

Tutorials are a good thing. They are. They can give you well-rehearsed examples of a pattern that works in a given coding language. Learning those patterns help you get the “feel”, the intonation of your code. Once your thumb is on that pulse, a good tutorial will let you fly free on your own from there.

But most tutorials online aren’t quite that good.

Instead of teaching you something, they give you a boilerplate stamp to copy, failing to explain the how and why of the code, or explaining it very poorly. This leads to a trap of doing tutorials one after another, never venturing out beyond their boundaries and unable to parse the reason why the methods they present are working.

This is why it’s often better to do the grunt work of discovery yourself. But if you must use a tutorial, do yourself a favor and consult the documentation to inform yourself of the how and why as well as the what and when.

Step Three: Polish the Turd

No duh, no one is great at coding languages right away. Yes, they are like a human languages, but at the same time, no one really speaks code “natively”. You won’t find anyone mumbling in binary in their sleep, offering George Carlin quotes translated into C#, or opining how their mother used to nag them const yourChores = (you) => you.laundry.sort() === true ? stayUpLate = true : grounded = true.

Even if somehow there was some bizarre cult who adopted a coding language as their official tongue, you can bet that their kids would have a rough go of it at first. I’ve heard my 2 1/2-year-old speak enough to know that, while she’s cute, she’s not exactly spouting Shakespeare.

What I’m trying to say is, most initial coding efforts in a language look like crap. They may work, eventually, barely, perhaps with unintended side effects and caveats, or they may take 153 lines to do what someone with experience can do with 10.

That’s perfectly okay. As long as you do it again.

And again. And… well, do it better, again.

Just keep polishing that turd until it shines. It can be done. Mythbusters proved it.

Step Four: Go Back and Learn It Again

So, feel like your a master of ES6? That your JavaScript logic-ing knows no bounds?

Well, just remember that there were a lot of numbers before 6, and there’s a good chance of a whole lot after, too.

Human languages change quickly. Even in a single generation, usage changes, connotation changes… even grammar ain’t what she used to be, no matter what some prescriptivist linguistic elitists will tell you. It’s a part of human culture: even for the French (but that’s a whole ‘nother story).

Coding languages make spoken ones look glacial.

Of course code changes rapidly. How else are we going to get to SAO or the Matrix in the future? Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash.

What was var yesterday is moreso const or let today, but there’s no telling if it might be also thus or accord or word tomorrow. That’s why it’s best to be flexible, and keep tabs on how your language(s) of choice are evolving. This is much easier to do than spoken languages, because organizations and programmers announce and debate what’s coming, and it’s far better to keep up rather than catch up.

If it were that way for English, I guarantee you that the phrase “those ones” would never have made it passed the beta. Who wants slang that’s longer to say than the normal phrase it’s replacing?

Last Tips

Here are a few last tips for coding (and language) learning that may help you:

- Getting a good general knowledge is a great first step, but it’s usually better to be a specialist rather than a generalist. Dig in deep on things that will be the most useful for what you want, and things that you feel particularly good at.

- Relatedly, there are million ways to do almost everything in code. Find a way that you like, that speaks to you, and use it like crazy. Own it. Yes, it’s good to also use other things that fit better, use fewer lines, or are more efficient as the case calls for it. But even the most well-rounded basketball player should have a go-to, bread-and-butter move for when they really need a clutch bucket.

- Keep a code journal. It’s like your own personal cheat sheet of cool code bits that you’ve written. That way you won’t have to dive again and again into the internet sea to relearn what you learned.

And that’s all until I learn much more about coding.